Mi favorito

My grandfather always called me his "favorita," his favorite, and I believed him for a long time. For the almost-three years I lived with him, when I was a little girl, my "tito" and I were inseparable. He was — he bragged, I actually have no idea if it's true — the only one who could calm me during one of my crying fits as a baby. He taught me sad Spanish songs, about cursed black eyes and lovesick nights, that I would sing in my angelic, clear 2-year-old voice to my stunned mother and aunt. He took me on my first trip to Montauk, dipped me — gently — into the freezing Atlantic Ocean, took me to his favorite bar, Gosman's, where he would order a gin and tonic and I would wear an enormous lobster bib and eat corn-on-the-cob. Apparently, my parents were on that vacation, too, but I don't remember them at all, and they aren't in any photos. I just remember Tito, making me laugh, making me happy, making me feel like the center of the universe.

But Tito did that with everyone. I later learned that he told my cousin Margaret, too, that she was his favorite grandchild — and once he got wind of that would say it to one of us in front of the other, and then act all embarrassed, like he had been caught in the act. But, you couldn't be mad at him. Because that was Tito's gift: he made everyone feel like his favorite. It's why his five grandchildren adored him. It's why his two daughters adored him. It's why every person who ever worked with him or who ever served him at a restaurant (believe me, the waiters and busboys would fight over who would serve him that day) or ever saw him dance to their music adored him. In his presence, and in his apparent delight in your presence, you felt suddenly that you were special. Actually, that's not it. He made you realize that you were special.

Ma (my grandmother) and Tito, in Cuba.

My Tito died a week ago, last Tuesday. I knew he was going to die. When I asked my father, a doctor, how long he had to live, he said maybe a week. My mother told me over the phone, as I was walking to a Lebanese place in the West Village. Later, my husband and I went to a concert at the Village Vanguard. The group performing — the Donny McCaslin Quartet — was also processing a kind of grief over the death of a loved one: their latest collaborator, the brilliant pop star David Bowie. There were times that the band leader couldn't speak, couldn't articulate his feelings about a certain song because of that loss. I felt that. And when his group played Bowie's beautiful, haunting "Warszawa," tears streamed slowly down my face, and I was thankful that it was sort of dim and that no one was looking at me anyway. Tito probably didn't know who David Bowie was, but he loved music, and he loved jazz — talking the ears off of the Afro-Cuban musicians who played at Victor's Midtown during a Father's Day brunch, requesting tunes, singing along, transported to some faraway place, some mythical, lost Cuba that no longer exists. I needed to listen to music that night — and it made me feel better.

***

I remember when my sister, Becky, got married. I was, with my other sister, Natalie, supposed to give a speech. And the best man said he was intimidated to talk after me because I was "a writer." But I gave a terrible half-of-a-speech. In fact, I barely said anything, and I rambled, and I felt terrible. Because how are you supposed to encapsulate everything that this person — whom you have known almost your whole life, since before you were 2, who is your best friend/kindred spirit/bosom buddy and who knows all those embarrassing, humiliating, shameful versions of you you try to exhume/suppress/forget — means to you. You can't. It's impossible. It's easy to write (or speak) about ... I don't know ... what a Bjork song means to you or the profundity of lingerie. I can pinpoint the moment I fell in love with David Bowie and how he changed my life, which I just wrote about after his death, a week before my grandfather's. But I can't do that with my sister, or with Tito, because they've always been there. How can I write about these people I don't know at all, or these inconsequential, removed things, with such passion and lucidity, yet can't adequately convey how much my family members, or my friends, mean to me.

I thought for a second, after that concert, that maybe these things can't be expressed in words, but only in the wailing of a saxophone, or the sad, dulcet tones of Bach Cello Suite. And I thought, then, after hearing this music I would maybe be OK, that after this little burst of sadness I could selflessly just celebrate the long life my grandfather had, be grateful that he didn't have to suffer too long, remember those good times. But, I would be alone in the bathroom and start sobbing, or hear a favorite funereal hymn and lose it. Or, my father would ask me if I wanted to say a eulogy at the funeral and I would panic or draw a blank or just be overwhelmed by the awesomeness of the task. My cousin and my uncle and my father ended up giving beautiful speeches. Yet, I want to try, too, because my grandfather meant so much to me, so here goes:

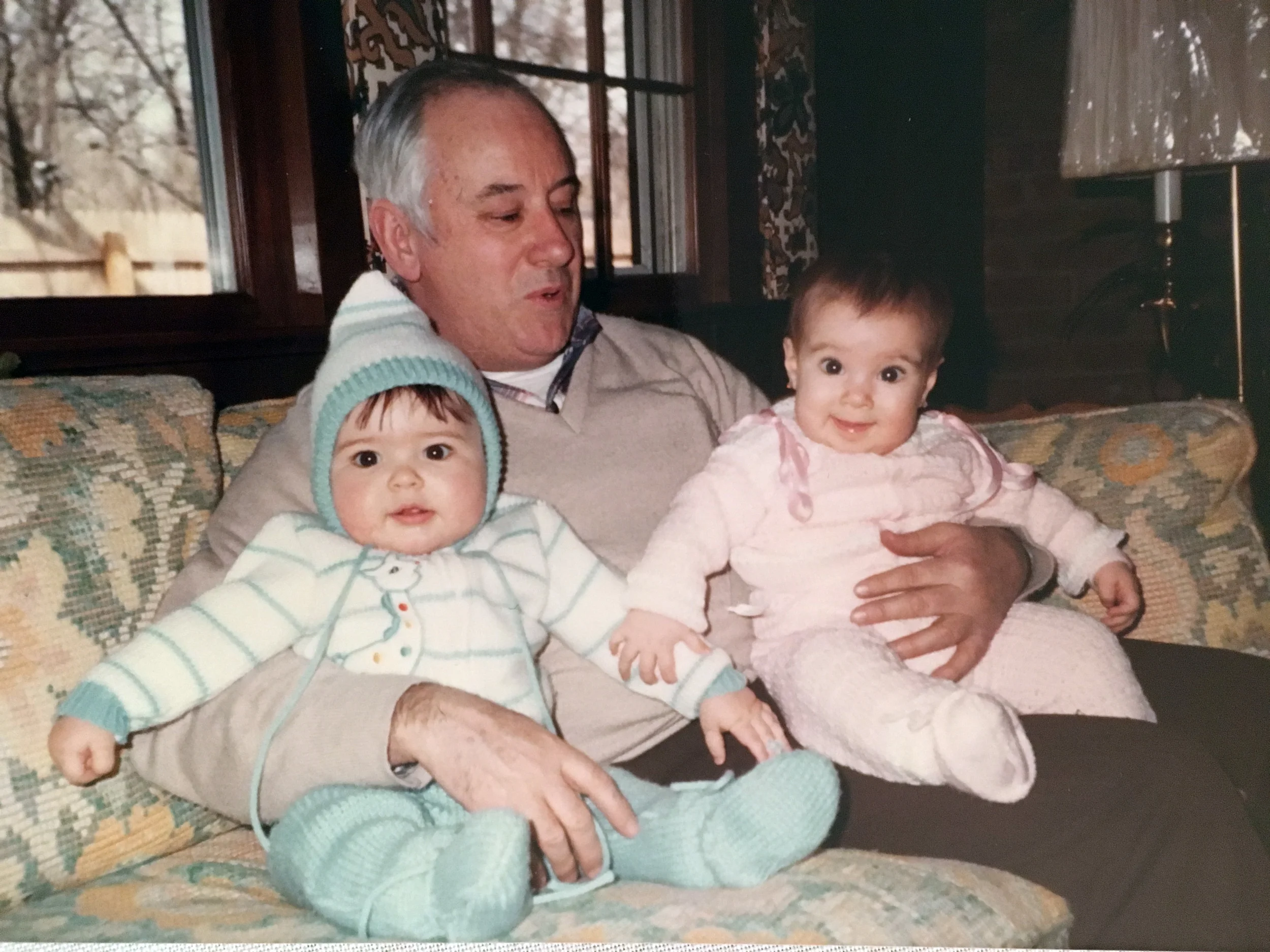

My cousin Billy (eight days my junior!), my grandfather, and me.

- His name was Camilo Arias.

- He had 11 brothers and sisters.

- He told me once that during the Spanish Civil War his father was in Cuba and he and his siblings lived practically like orphans back home, hungry, killing whatever animals in the farm or woods they could for food (this may be my own imagination's, or my grandfather's, exaggeration, but it seems fitting with his character).

- He could speak Spanish, French, Portuguese, and even a little Chinese, the latter of which fascinated us grandchildren, and he loved to show off the phrases he knew. He barely, however, spoke English.

- He worked until he was 80 years old.

- The love of his life, I think, was Cuba, where he lived intermittently during his youth and where he met my grandmother, a 17-year-old trouble-maker who looked like Elizabeth Taylor and gave him two beautiful little girls. (She's still alive.) He longed to go back before he died, but wouldn't do so until it became a democracy.

- He made the best cafe con leche — which he prepared very methodically and with great care — and on my wedding day, he woke up early to whip me up a cup, which he served along with my favorite challah bread that he and my grandmother had transported from New York to Pittsburgh for the occasion.

- He loved the ocean.

- He was a great dancer.

- He would take me on drives, when I was little, along the coast, to see the docked, covered boats bobbing up and down in the water, which was my favorite thing in the world, and we even made up a song about it, which went like this: "Vamos a ver/ los botes tapeditos/ trim bi li dim trim trim."

- He was a bit of a trickster, and would sit at player pianos pretending to play Chopin and make faces in pictures with my grandmother and do anything to make me and my sisters and cousins laugh hysterically. He also let us ride rolling around in the back of his station wagon, which my mother hated but we found thrilling.

- He was extraordinarily kind and generous and spoiled us rotten.

- I miss him so, so much.