There's a starman waiting in the sky ...

"This was not supposed to happen. Ever."

That was my reaction, too, when I heard the news today, that David Bowie — that beautiful, elastic, shape-shifting mad musical genius — had died, this morning, of cancer. The man had, just days ago, dropped his latest album, "Blackstar," as searching and radical and inquisitive and forward-looking as anything Bowie has ever done. He had a new musical, "Lazarus," playing Off Broadway. He starred in a bracing video (below), a parting gift of sorts, where he writhes blindfolded on what looks like a hospital bed, and even does a kind of robot dance. Who knew he was battling cancer the whole time? Bowie's relentless pursuit of art, the breakneck speed with which he ran toward everything new and exciting, made illness seem inconceivable, and his death like a vanishing or disappearing act. Surely, he had just shed one exterior for another. Surely, Ziggy Stardust/Aladdin Sane/The Thin White Duke could not really be mortal. But, he hadn't. He was. And, it's so, so weird.

I came to Bowie rather late. I was in high school, and my best friend had rented "Velvet Goldmine," Todd Haynes' high-octane surrealist tribute to glam rock. (Fictionalized, but the lead character is an obvious Bowie stand-in.) I had never seen anything so strange and beautiful and sexy. It felt dangerous and reckless and freeing watching men kiss one another and transform into glittery beings and perform this shiny, electric, perfect music in platform shoes and eye makeup. I was never the same.

In college, Bowie's music followed me everywhere. At a coffee shop, studying to the crunchy riff of "Rebel, Rebel"; in a movie theater, as the plastic-soul incantations of "Young Americans" played over the closing credits of "Dogville"; in a friend's room, listening to her favorite song in the whole universe, "Starman," which I assumed was about the slightly unreal Bowie himself ("there's a starman waiting in the sky/He'd like to come and meet us, but he think he'd blow our minds"). I encountered photos of him with long hair and flowing folkie dresses; with a rust-colored mullet and face paint and metallic silver jumpsuit; in a dapper vest and crisp collared shirt and jaunty fedora. And each time I couldn't believe this was the same artist, that one man could have so many lives, could have such a prodigious capacity for imagination, could conjure so many worlds and personae.

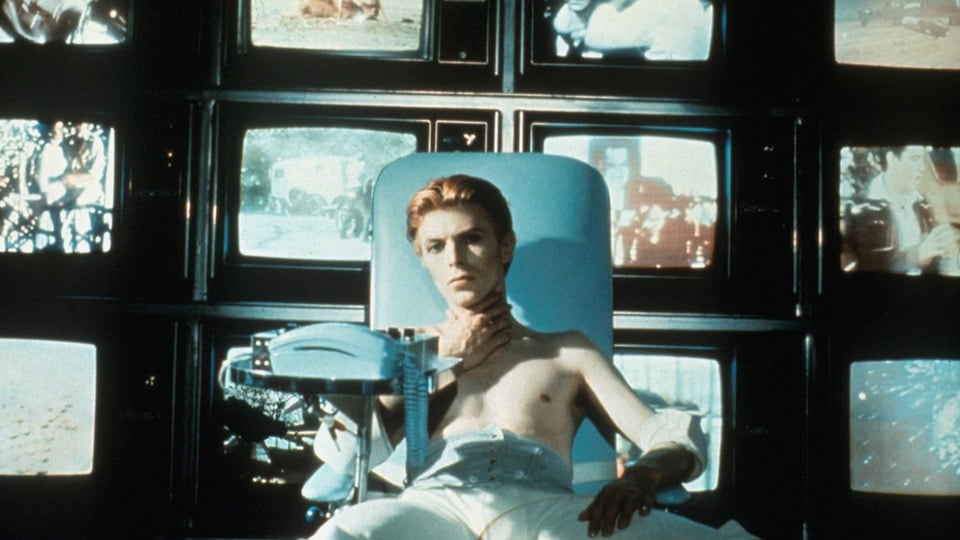

I haven't even mentioned Bowie's acting career, but it makes sense that someone so fluid could morph so seamlessly into Andy Warhol (in "Basquiat"), or a romantic cello-playing vampire ("The Hunger"), or a spandex-clad goblin king ("Labyrinth"), or even Nikola Tesla ("The Prestige"). And there's, of course, his eerie, other worldly creature flung from space in "The Man Who Fell to Earth," a film that used his extraterrestrial beauty and hauteur and intoxicating impenetrability to wondrous, heartbreaking effect.

That slipperiness could make Bowie seem cold and alien, plastic and fantastic, even distrustful. But it always conveyed freedom to me: the freedom to be weird, to become whoever or whatever you want, to slip in and out of various guises and identities, unbound by age or gender or place or time or labels. That openness has to be why his music is so challenging and surprising and wonderful — why he continued pushing and experimenting till the very end. But it's also why it will live forever: because it gives us more ordinary dreamers and weirdos the permission to go in search of, or build our own, more adventurous, fabulous, and expansive worlds. RIP David Bowie.